As key companies and entrepreneurs announce plans to bid for selection to the Indian government’s Production Linked Incentive scheme, Dipak Sen Chaudhuri gets excited about what this could mean for India’s battery industry and long-term energy security.

There is a ‘buzz’ in the air! The ultimate names in Indian entrepreneurship— the Ambani’s and the Adani’s— have both formally bid for selection under the ‘Production Linked Incentive (PLI)’ scheme of the Government of India, for setting up manufacturing units in the country producing ‘Advanced Chemistry Cell (ACC)’, as it has been defined. Also in the bidders list are Samsung, Panasonic, a Toshiba-Denso-Suzuki conglomerate; a cash-rich Indian company, Rajesh Export— one who has, to date, been in the gold and diamond jewellery business. LG and CATL are also there, though the rumour is that their interest may be a little less than serious.

As I have been writing over the last few years, the Indian government authorities had quite correctly assessed that promotion of renewable energy and electric vehicles would be vital to securing the country’s long-term energy security. Central to this aspiration would be the availability of robust and cost-effective energy storage solutions that must be manufactured in the country itself. Given the hard stares that China and India quite often exchange, perhaps because of their respective domestic political compulsions, it would be essential for India to be free of any ‘China dependence’— at least on this vital aspect of national infrastructure. The bureaucrats, under advice from technocrats, have been engaged, for the past few years, in figuring out the role the government can play in addressing the problem.

Therefore, in line with the government’s oft-stated visions, ‘Atma Nirbhar Bharat’ (self-reliant-India) and ‘Make-in-India’, the authorities have now issued formal notification asking for ‘Request for Proposal’ (RFP) documents. This is to facilitate selection of private investors interested in setting up manufacturing facilities that produce ‘Advanced Chemistry Cells’. The selection would be based on the financial parameters of the bidder and the technology they propose to manufacture. A formula has been designed to rank the bidders on the combined score of these two elements.

The ultimate objective of the government mission is to make cells manufactured in India to be globally competitive for both technology and cost.

The ultimate objective of the government mission is to make cells manufactured in India to be globally competitive for both technology and cost. Whilst on one hand, several policy interventions have already been issued to promote electric vehicle penetration across the country; the current manufacturing incentives are directed towards India achieving a total self-reliance long before 2030. This date is when the domestic requirement of advanced batteries is expected to reach a level that can support a manufacturing capacity of up to 50GWH. It is to be noted that the government has announced similar PLI initiatives in 10 ‘key sectors’ that include telecom, renewables, electronics and advanced batteries. The outlay specific to batteries is INR 18100 million ($2.4 billion), which is a significant amount of money. It is to be noted that the subsidy will be limited to a cumulative 50GWH manufacturing capacity, and no individual bidder can receive benefits beyond 20GWH.

The selected bidders would be entitled to receive financial benefits in the form of a subsidy on every sale they make. To qualify, one of the first criteria they would be required to satisfy is setting up of a unit with a minimum of 5GWH of annual manufacturing capacity, which may be developed in phases over a five-year window. In addition, the successful bidder will have to establish a minimum value addition at the cell level of 25% and on the overall pack level 60%. Financially, the bidder will need to have a credit rating of at least CRISIL AA+ or ICRA AA+, if incorporated in India; and for companies incorporated outside India S&P BB+, FITCH BB+ or Moody’s Ba1, from at least two credit-rating agencies. Additionally, the bidder will have to demonstrate a net worth of INR 225 crore ($30 million) per GWH.

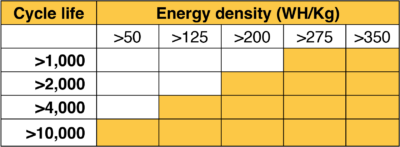

Coming to the chosen ‘advanced chemistry’ aspect, the request for bids is totally technology agnostic. Instead, it defines a matrix (Table 1) of the proposed technology in terms of energy density and cycle life.

In order to qualify as ‘advanced’ chemistry and be eligible for subsidy, the proposed technology has to fit in to any of the shaded slots in Table 1. Also, the financials get better as you move up on energy-density and/or cycle-life.

The government has laid out an open invitation and the bidders are also known. Where does this take the Indian energy storage industry? When the houses of Ambani and Adani announce their intent, they send very strong signals. The combined personal net worth of the two gentlemen is of the order of $140 billion, with Mukesh Ambani, the owner of the Ambani empire, ranked as one of the ten richest individuals in the world.

Reliance Industries, the behemoth owned by Ambani, has a current market cap of $200 billion. Moreover, Reliance group has established itself as the game changer in the Indian market. Exactly 50 years ago, Mukesh Ambani’s father, Dhirubhai Ambani, started the group that eventually came to be known as ‘Reliance Industries’. Dhirubhai was then a relatively small textile mill owner from Gujarat, the western state of the country from where Prime Minister Narendra Modi hails. Dhirubhai swiftly moved in to the polyester industry and forged ahead of all competition on his way to setting up the Reliance Empire. Moving into petroleum refinery and petrochemicals, Reliance, under the leadership of Mukesh, is forging ahead, riding on an explosive growth in the Indian telecom industry, and has big aspirations in retail.

In every industry the Reliance group has entered they have completely changed the rules of the game. Sheer financial brute-force has enabled them to take away customers from their competition. One of the key features of their growth has always been their close alignment with central government, irrespective of which political party has been ruling. It is supposed to be coincidental that many of the government policies, particularly import duties etc., were changed— and Reliance has been a major beneficiary of them.

The Adani’s came later. Initially they were in commodity trading, and later into ports, power (including renewable power), and the purchase of large coal mines in Australia. They also come from Gujarat, and while they may not have the weight of the Reliance group, they still have shown sufficient bandwidth to get into long-gestation investments. The information I get is that Reliance is dead serious on this and, behind all this excitement, is quietly and vigorously working out its plan. In fact, there are some news reports around that they have started to secure small parcels of land across the country— presumably to set up the charging infrastructure.

In this enormously competitive field, where product reliability and robustness get tested every moment, any handicap in performance or life would take the entire venture backwards

The challenge faced by the Indian houses will be in two major directions. The first would be technology. Whatever chemistry they select, it would have to be state-of-the-art and evolving. In this enormously competitive field, where product reliability and robustness get tested every moment, any handicap in performance or life would take the entire venture backwards— which an organisation like Reliance can never allow to happen to their brand.

The second would be in establishing the right supply chains. It is not enough that the government of India is trying its best in setting up an international ore and finished-metal import house. Material will be sourced through possible bipartite agreement between the global ore producers and the Indian trading house, under the sponsorship of the government. The challenge would be in selecting the processing technology for conversion of raw materials, to the right quality for use in the cell active material preparation, at the best cost. Large chemical plants specialising in these chemistries are currently dominating this field globally. Would the Indian companies go for backward integration and also include this in their project planning?

Electronics is another aspect. India, like the rest of the world, is facing an acute shortage of chips for the assembly of electronic devices. The advanced-chemistry cells invariably require electronic management systems and, while the management system know-how may easily be developed locally, another concern remains if China continues to be the source of components for them. The Indian companies involved here are known to have deep pockets, but how deep they are may get tested— unless the supply chain is top of their agenda.

It is on these grounds the overseas companies have a major advantage— both in technology and supply chain. However, given their fetish for technology confidentiality, manufacturing cells in India will not be a prospect they would relish. Administratively, running a company in India still has major challenges. However, surely the Indian market size is something no manufacturer would like to overlook. So, these are very exciting times— a period of anticipation. It remains to be seen how the picture unfolds.

A final note on where this leaves the Indian battery, mostly lead-acid, manufacturers. They have a very conspicuously muted presence. For one it clearly seems that they do not have the appetite for such big-ticket expenditure. Second, they do not have the technology to compete with the current industry standards. In their logic, perhaps they are better suited to the role of aggregators. The country will still need large-scale aggregators to meet the diverse needs of the users. Exide Industries has set up a very modern facility— a joint venture initiative along with Leclanche, Switzerland— also in Gujarat, for pack building. Their facilities are ready to go, can handle a large amplitude of kWh ratings, and are suited to handle diverse configurations— cylindrical, pouch and prismatic. Amara Raja Batteries has also announced setting up a pilot lithium cell manufacturing facility, with technology from the Indian Space Research Organisation. To date, not much more is known about this venture.

I know that lead-acid works and it comes in at around 50% of lithium battery cost.

Does this mean the end of the road for lead-acid technology— at least so far as vehicular application is concerned? According to this correspondent the answer is certainly no! India remains a poor country and the overwhelming majority of the Indian two-wheeler owners remain financially challenged. For them, a lead-acid solution that meets their expectation of two years assured life would be more than enough to make them happy to stick to the time-tested lead technology. I know that lead-acid works and it comes in at around 50% of lithium battery cost. It does give an optimal solution between battery cost and performance. So, the Indian lead-acid manufacturers have a chance here. Go for it! The two-wheeler and three-wheeler market will remain yours!